How data helped me solve a decades-old family puzzle

I grew up knowing exceedingly little about my grandfather. He died before I was born, I didn’t know him personally, I didn’t know his family history, I didn’t know what happened to him during the war. And to be honest, I was never all that curious — it was just kind of a blank, a subject not really talked about in my family. Not because it was traumatic, but because no one knew anything. We knew he was a Holocaust survivor, and we knew he had come from someplace called ‘Sosnowiec’ but that was it, that was the extent of our knowledge. It was something that was ‘important’, of course, but in a grand and untextured sense; the particulars were never emphasized. And I easily could have gone my entire life without exploring further.

The first time I went to Poland was by chance: I was living in Lithuania on a Fulbright Fellowship and got invited to Krakow for Rosh Hashanah. While I was there I visited Sosnowiec — not out of any great longing, but more like an errand. My father had gone through some old papers in the closet and retrieved an address: Małachowskiego 12. I went to the building, I took some photos, I snuck inside, and then I left. At that point, I had no reason to think I’d ever return.

Over the next few years, I spent a great deal of time in Poland, doing research unrelated to my family. My father kept mentioning that our family in fact owned this building, that I should look into it, but there was never any urgency; eventually, in 2015, he got tired of my laziness and faxed me all the documents he had to Krakow, where I was spending the summer. And going through the documents, piecing together the narrative, seeing how my grandfather had tried — and failed — to reclaim what was his, what had belonged to his family, I was unexpectedly moved: for the first time in my life, I felt a sentimental attachment to my grandfather. And I was in the position to pick off where he left off, to resume his mission. I hired a lawyer and began the reclamation effort.

I wasn’t overly familiar with JRI-Poland back then, but my lawyers were. They contacted Stanley Diamond (for reasons I don’t fully understand they called him ‘the man from Montreal’) and requested a list of all records listing ‘Kajzer’ and ‘Rechnic’ (my great-grandmother’s maiden name). And the records were inspiringly expansive. Birth records, marriage records, death records — it was a meticulous spreadsheet of more than thirty pages. It was eye-opening personally, of course, but beyond that, it was so moving that such a database existed, that such records were maintained and have been made accessible. It is a remarkable service, and represents the highest level of communal dedication and preservation.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that these records changed my life, and in the most surprising ways. A year later, I met a group of treasure hunters — it’s a long story; you can read it in the book — who were obsessed with a man named ‘Abraham Kajzer.’ I suspected we might be related, as Kajzer was from Bedzin, and my family was from Sosnowiec. I was able to confirm this suspicion only with the documents JRI had provided: I was able to construct a family tree and I could see that Abraham and my grandfather were in fact first cousins; Abraham was my grandfather’s closest surviving relative. Word got out among the treasure hunters that I was Kajzer’s kin, and I became a celebrity, and it was at that point I decided I would try and write a book about all this, about reclaiming the building, about the treasure hunters, about Abraham, about my attempts to be in conversation with my grandfather.

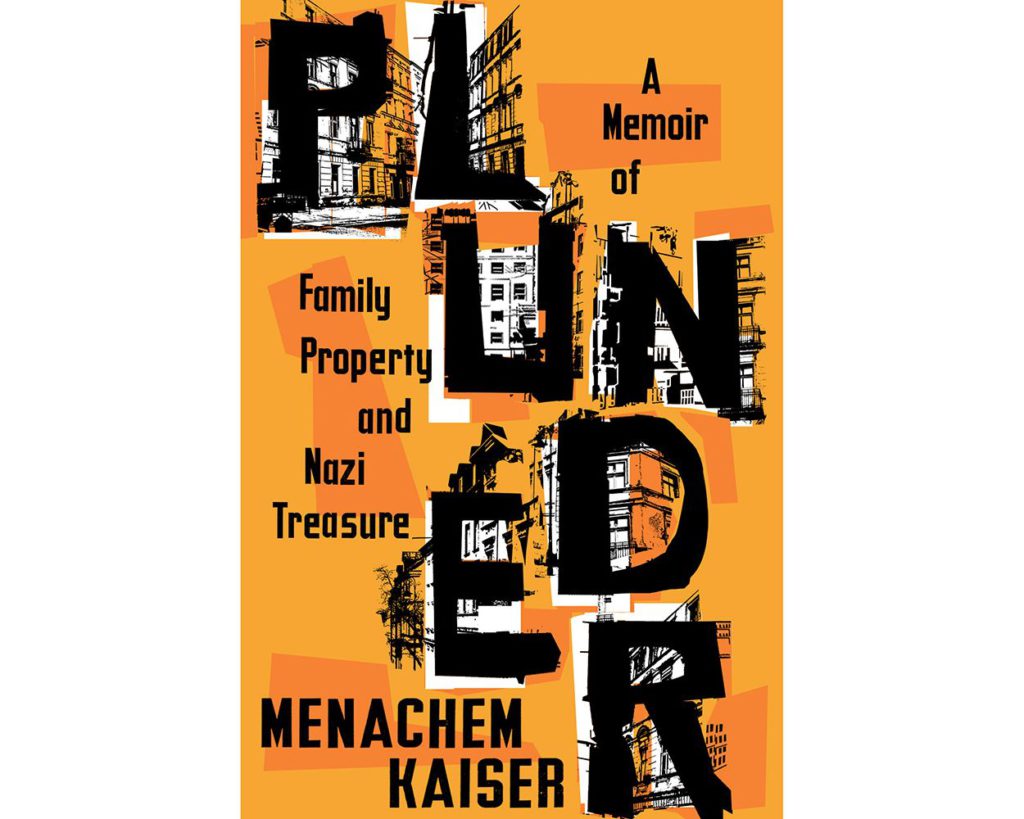

That book, Plunder, was released in March 2021. The records JRI-Poland provided were the foundation on which the narrative rests. And I am forever grateful.

Plunder has been named, A New York Times Critics’ Best Nonfiction Book of 2021, has received the Canadian Jewish Literary Award for Biography, and most recently, The Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature. It can be found wherever great books are sold.